| |

ROCHESTER MAGAZINE

Paralyzed at 27, Andy Anderson is living a full life

58 years ago, Andy Anderson fell out of a tree and was paralyzed. In an instant, a quadriplegic. It barely slowed him down.

Written By: Jennifer Koski | Sep 3rd 2020 - 6am.

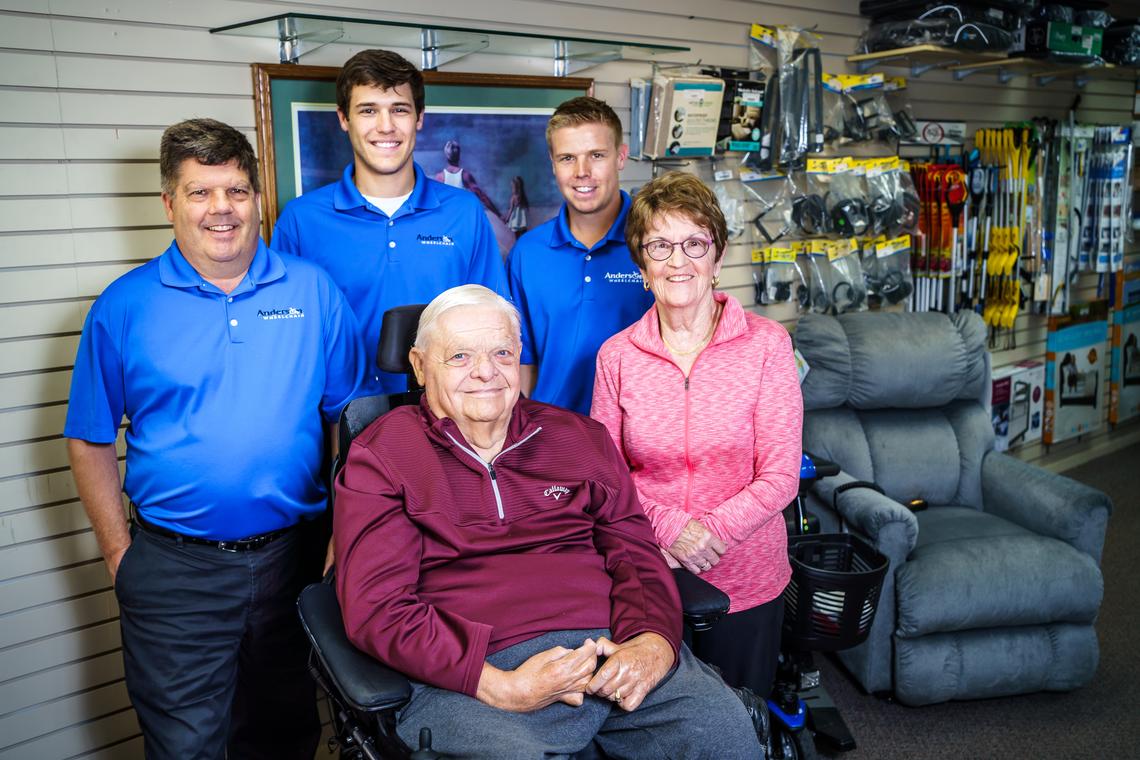

Andy and Gretchen Anderson

It was a cool and sunny afternoon in September 1962 when James “Andy” Anderson’s life changed forever.

The lifelong Rochesterite was in his backyard prepping his guns for pheasant hunting while his wife, Gretchen, put their kids down for a nap. Next door, a neighbor was getting ready to prune a tree. Could Andy give him a hand? Andy—a 27-year-old insurance salesman and father of two, a former Rochester hockey star, a former soldier who served in Korea—was happy to help.

He headed to the neighbor’s tree. Hoisted himself onto a limb six feet off the ground. Reached out with the saw to trim an adjacent branch.

Inside the house, 22-month-old daughter Kim wasn’t sleepy. In fact, she was trying a new trick—rocking back and forth in her crib to make it move closer to her 9-month-old brother.

“I thought, ‘I want Andy to see her do this,’” Gretchen recalls. “So I headed outside to get him. And that’s when I saw what had happened.”

The branch Andy had been standing on had snapped. His foot, caught in the joint between limb and trunk, had flung the rest of his body to the ground, headfirst.

“If I’d been up higher, I could’ve flipped over,” says Andy now, reminiscing about that day. “But instead, I snapped my neck at the base of that tree.”

A Mayo Clinic fellow who lived down the block had already been summoned. He directed the neighbor to call an ambulance. By the time Gretchen made it to Andy, she could hear the siren.

A Mayo Clinic nurse, Gretchen knew Andy’s accident was serious. But it wasn’t until the ambulance arrived that she knew how serious it was.

“I heard the driver say, ‘Get the circle bed ready,’” says Gretchen. “And I knew what that meant. Andy was paralyzed.”

Andy Anderson and Gretchen Dale met through mutual friends in 1956. She was an 18-year-old Lourdes high school senior. He was a 1954 Rochester High School graduate getting ready to serve in the Army after a stint at Rochester Junior College.

By the time Andy left for basic training and Gretchen headed to the Minneapolis School of Nursing that fall, they were an item. When Andy returned home from Korea in 1958, he proposed at a pizza place not far from Gretchen’s campus. (“I think I said, ‘You want to get married?’” says Andy. “It was very romantic.”)

The couple married in 1959 and bought a home in northeast Rochester. They were, by all accounts, living the American Dream.

There was work. Gretchen took overnight shifts at St. Marys Hospital, while Andy worked as an agent for Northwestern National Life Insurance Co.

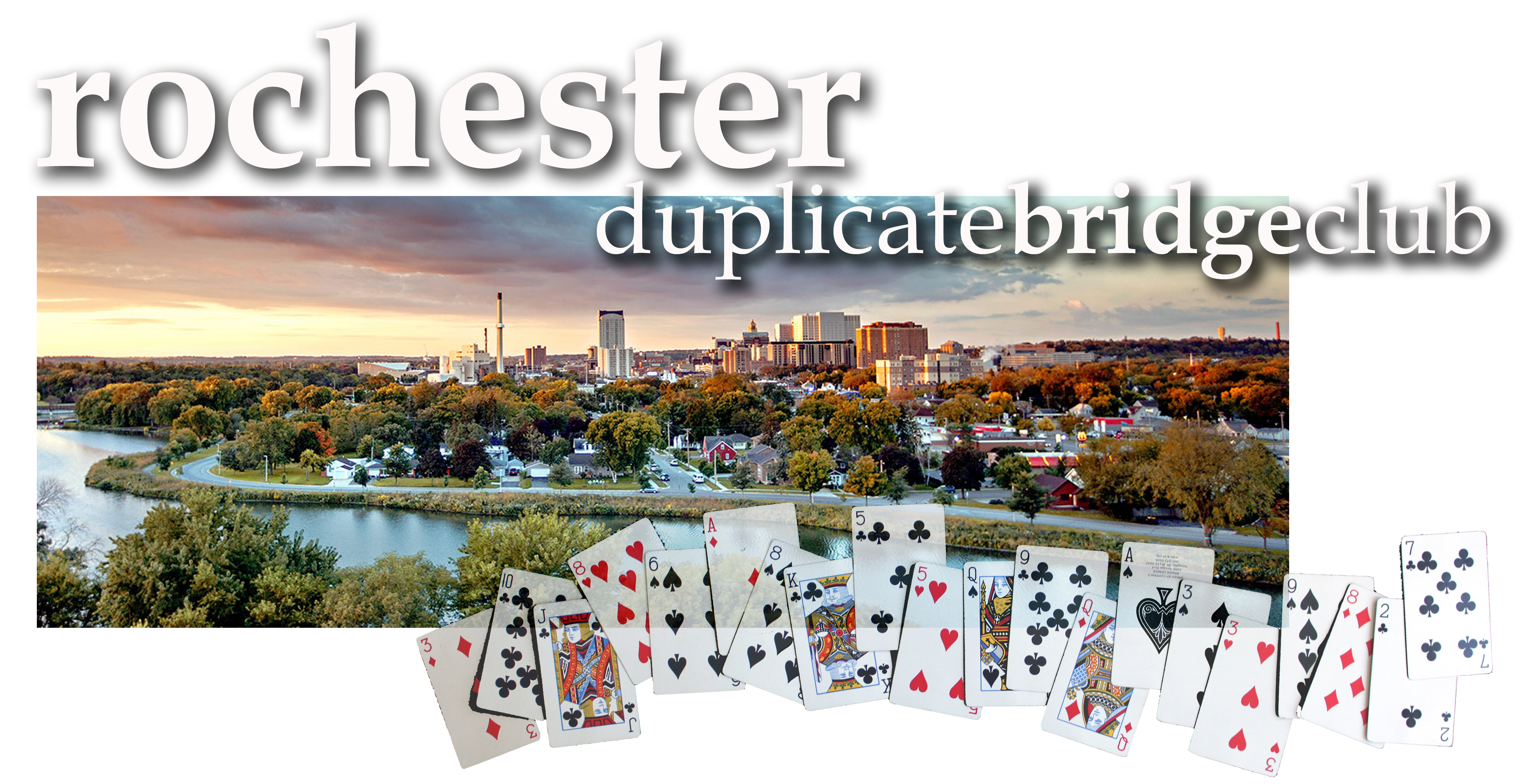

A mid-1960’s article promoted Andy’s new copying, addressing, and mailing service. The business was made possible through a pilot program designed to help injured people return to work. Photo by Joe Ahlquist.

A mid-1960’s article promoted Andy’s new copying, addressing, and mailing service. The business was made possible through a pilot program designed to help injured people return to work. Photo by Joe Ahlquist. A mid-1960’s article promoted Andy’s new copying, addressing, and mailing service. The business was made possible through a pilot program designed to help injured people return to work. Photo by Joe Ahlquist.

A mid-1960’s article promoted Andy’s new copying, addressing, and mailing service. The business was made possible through a pilot program designed to help injured people return to work. Photo by Joe Ahlquist.

There was hockey. Andy, who’d been a star player in high school, had gone on to play amateur league for the Rochester Colts while in college. When the Colts disbanded, he reorganized the team to create and play in the Southern Minny League.

There was their first child, Kim, followed just 13 months later by a son, Jay.

“And then, a year later,” says Gretchen, “Andy fell from the tree and got hurt.”

The news at the hospital was grim. Doctors told Gretchen that Andy had a spinal cord injury—a partial C6-7 laceration.

He was unable to move anything but his head.

“They told me my husband would never walk again. That he had five years to live,” says Gretchen. “And then they asked, ‘Do you have any questions?’”

“I thought, ‘Questions?!’ I said, ‘There are so many things he won’t be able to do. Who’s going to play ball with the kids? Who’s going to be their dad?’”

“The doctor said, ‘Your children will have friends to play with, but he will always be their dad.’”

Ultimately, it was thoughts like these that steeled Gretchen’s resolve. Instead of focusing on what Andy wouldn’t do, she became intent on what he would do.

“I told him, ‘Your life’s not over,’” she recalls. “’You have to do what you have to do to get well because you have two little kids at home.’ To be honest, I wasn’t very sympathetic. He had a lot to live for, and sometimes we just had to go over that again. But, really, he never got too down. He’s never been ‘poor me’—never from the beginning.”

Andy would be in the hospital for the next 18 months.

It was 18 months of procedures and physical therapy that allowed Andy, first, to sit up. Then allowed some movement in his upper arms. More surgeries, including tendon grafts to improve grip strength, gave him some control in his hands.

Through it all, Andy was a willing participant. “Whatever the doctor said, we said yes,” he remembers. “We never doubted their word. We never second-guessed them. My hands don’t look the best because of all the tendon transplants, but they work.”

Though doctors had given Andy only five years to live, the couple didn’t dwell on numbers.

“As his health progressed and he was discharged from the hospital, we didn’t really think about ‘five years’,” says Gretchen. “We knew we had to keep fighting and provide the best life for our two kids.”

Gretchen, who’d never return to her job at St. Marys after the accident, put her nursing skills to use at home as Andy’s caregiver. For his part, Andy was committed to living as full and independent a life as possible.

“Say I’d have to put my shirt on,” he remembers. “She’d say, ‘Want help with that?’ But, no, I didn’t. It would take me an hour and a half to button my shirt, but I had to do this myself. It was my therapy.”

A full and independent life also required a new home.

Because Andy couldn’t return to the family’s existing house—which wasn’t wheelchair accessible—he spent months in the hospital designing a home that would accommodate his life as a quadriplegic.

It would include wide doorways and rooms to accommodate his manual wheelchair. Hydraulic assist lifts to help him get in and out of bed and the bath. An elevator alongside the stairway.

A new home, though, was just one step. Andy would also need a job—and fast. At $203 a month, his disability payments weren’t nearly enough to support a family of four and 18 months of hospital bills.

The family worried about how Andy would find work. And then opportunity struck. The Minnesota Division of Vocational Rehabilitation was launching a pilot program with St. Paul’s 3M company. “They wanted to get people who were injured back working,” says Andy.

He was one of two people chosen for the program’s launch.

Andy was given $1,500 worth of equipment and supplies to start a copy, addressing, and mailing service for small businesses. With Gretchen’s help, he converted a portion of the living room into an office and took orders over the phone. He managed the equipment with the partial use of his hands.

The business was so successful that 3M sent Andy to Denver in 1966 as a delegate to the National Rehabilitation Conference, where he demonstrated several of the office machines.

Working as a team, Andy and Gretchen expanded their business lines to include magazine subscriptions, personalized Christmas cards, and wedding invitations.

An October 1968 PB article recognized Andy’s role as president of the Hiawatha Valley Chapter of the Paraplegia Foundation. Photo by Joe Ahlquist. An October 1968 PB article recognized Andy’s role as president of the Hiawatha Valley Chapter of the Paraplegia Foundation. Photo by Joe Ahlquist.

Through it all, Andy also managed to be the father that Gretchen had dreamed he could be.

“I couldn’t play with the kids,” says Andy. “I couldn’t get down on the floor with them. But we could play games—we played chess. I’d tell them where to move my pieces.”

To Jay and Kim, growing up with a quadriplegic father was the norm.

“To me, he wasn’t any different than any other dad,” says Jay. “He even coached my hockey team. Practice was at Silver Lake and he’d say, ‘Jay, get my wheelchair out of the back, push me out on the ice.’”

Daughter Kim agrees. “My dad was no different than other dads other than he couldn’t walk,” she says. “We had a cabin. We went boating. He snowmobiled.”

Life went on for the family of four, providing a model of success for what is possible in the face of serious injury.

Then, one day, Dr. Ann Schutt called and said she’d like to meet with Andy and Gretchen. The doctor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Mayo Clinic had a request: Could Andy talk to a new spinal cord injury patient? Tell him, maybe, that things aren’t that bad? Tell him about Andy’s life—about his family, his job. Show him the new normal really can mean a rewarding and full life.

Andy said he’d be happy to help.

“Many people who suddenly find themselves with a disability have difficulty adjusting to it,” he says. “We thought another handicapped person might be able to talk to me better about their problem. I told Dr. Schutt to give me a call anytime she needed help.”

Andy didn’t know it then, but it would be a service he’d fill weekly—sometimes two to three times a week—for decades to come.

And though they’d built a life on teamwork, this was one area where Gretchen couldn’t help. “It was always so important that I didn’t go,” she says. “If I were to say to someone who was just paralyzed, ‘We’re going to help you. Things will get better,’ it doesn’t work. But if Andy talks to them, it makes a difference.”

It would also lead to a career the couple never saw coming.

As Andy’s partnership with Dr. Schutt grew, another request came from the Clinic. Would the couple consider selling equipment for people with injuries like his?

Mayo Clinic wanted somewhere local to send patients, and promised to support the Andersons if they undertook this venture.

Andy and Gretchen knew firsthand that supplies were difficult to find in Rochester. They had, after all, purchased Andy’s wheelchair from the only local source available—a wholesale supplier who offered no customer service.

“When we picked up my first chair,” remembers Andy, “there was no conversation, no explaining how it worked. Just, ‘Where’s the check?’”

And when he needed a repair, he was given one option. “I’d worn out the tires, so I went back to the doctor and said, ‘Where do I get it fixed?’ He said, ‘Go to the bike shop—they can order something that should work.’”

At the time, putting a bike tire on a wheelchair did work … but it wasn’t ideal. And wheelchairs need more than tires. “They didn’t have all the parts,” says Andy. “It might be a bearing you needed or an upholstery repair. And there was no place to get those things fixed.”

Andy and Gretchen started with crutches, canes, and walkers.

Working from their basement, the therapeutic supply business was a true family affair. Gretchen and Andy’s dads helped put together crutches. Gretchen’s mom made exercise sand bags. Andy’s dad helped with the books.

But the need was greater than that.

In 1971, four years after launching their business, they added wheelchairs. By ‘74, they’d designed and built a larger home on North Broadway—with a separate, walk-in showroom and elevator-accessible office—to accommodate the growing business. And four years after that, Anderson Wheelchair moved to its current location on Second Street SW, across the street from St. Marys Hospital.

The Second Street location had been the All Soft Bakery. When Andy and Gretchen first toured it, they were wary about making the space—which was filled with a room-sized cooler and ovens—into the storefront they needed.

“There was flour all over the place!” Gretchen remembers.

But a business-minded customer who’d become a friend, who recognized the power of a location directly across the street from St. Marys Hospital, encouraged them to make the move.

It was a smart one.

The new space allowed them to expand their business, selling and servicing wheelchairs in addition to stocking adaptive equipment, from one-handed cutting boards to card shufflers to canes.

Armed with a powerful location and an even better relationship with Mayo Clinic (who, Andy says, “was always very good to us”), their model has worked for more than 40 years.

Despite a busy work and family life, Andy filled his plate with civic commitments.

He continued to work with Dr. Schutt to counsel and help people with spinal cord injuries.

He served as the president of the Hiawatha Valley Chapter of the Paraplegia Foundation.

Was pivotal in bringing a pioneering driver’s training program to Rochester—the first public program of its kind in Minnesota—for handicapped drivers, providing special hand controls for braking and accelerating. (And was one of the first to get his license through the program, five years after his accident.)

Lobbied the Rochester City Council to request building codes to allow disabled people to better navigate the city. (And had to be carried in his wheelchair up the steps to attend that meeting.)

Coached Rochester Youth Hockey—where he was on the ice in his wheelchair at every practice and game.

Helped raise money for the construction of Graham Area. Served as director of Rochester Mustang Hockey Association. Treasurer of the PTA.

It’s no wonder, then, that Anderson received the Jaycees’ Outstanding Young Man award at age 35. (His nomination form read, in part, “Andy practically ignores his own situation as he concentrates on solving the problems of his fellow man.”)

More awards followed. Like the 1990 SEMCIL recognition award for outstanding contributions for empowering persons with disabilities in Southeastern Minnesota. And the Mayor’s Medal of Honor from Rochester mayor Chuck Hazama in 1992 in recognition of outstanding efforts in behalf of services to the disabled.

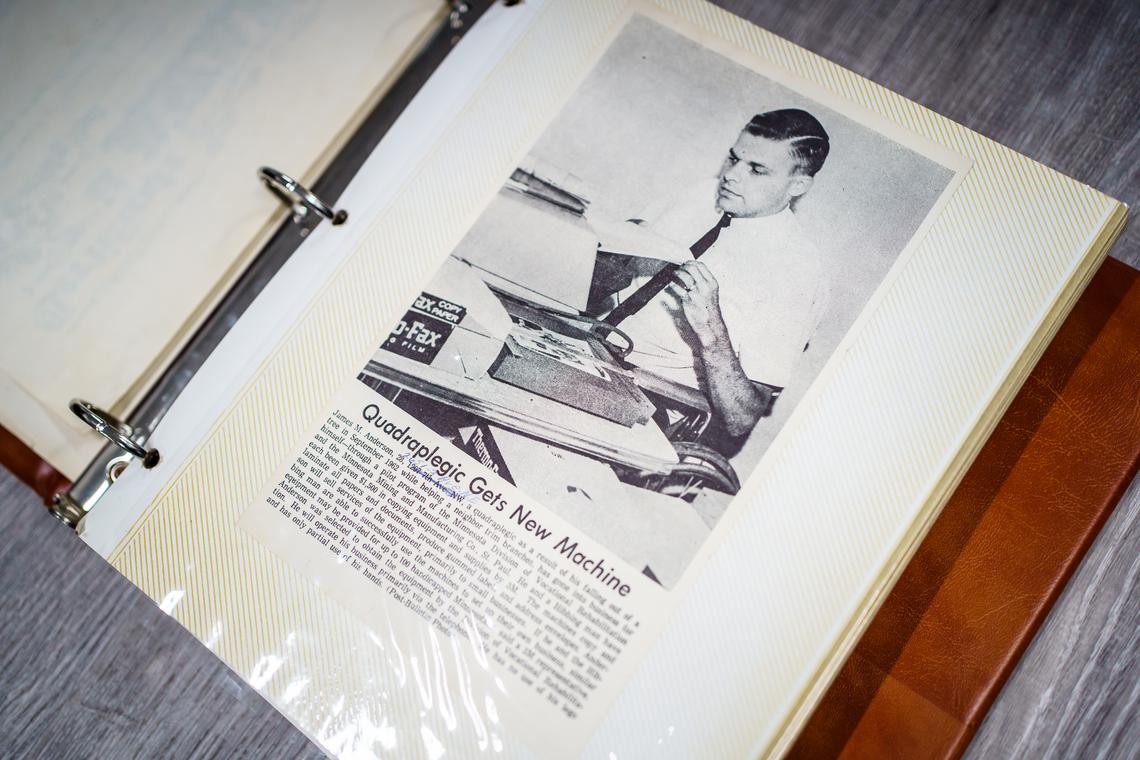

Andy and Gretchen have been the center of Anderson Wheelchair since they first opened their basement doors in 1967. And while the couple is now technically retired, you’ll still find them at the office at least once a week.

Kim and Jay—who were involved from an early age (“there were no child labor laws then,” jokes Andy)—moved onto their own interests after college.

But they were pulled back. Kim’s husband, Steve, joined the business in the late ‘80s. A few years later, in 1991, son Jay returned to work alongside his family.

Today, the third-generation Anderson Wheelchair has nine employees—three of whom are family. Though Steve retired in 2019, Jay’s sons, Tyler and Drew, are now integral members of the business.

And they’ve never been busier.

Anderson Wheelchair now sells and services about 1,000 chairs a year, most custom ordered. “We measure our customers like we’re making a suit for them,” says Jay.

Family affair: Andy and Gretchen with son Jay (left, now president of Anderson Wheelchair) and grandsons Drew and Tyler, who also work in the business. Photo by Joe Ahlquist. Family affair: Andy and Gretchen with son Jay (left, now president of Anderson Wheelchair) and grandsons Drew and Tyler, who also work in the business. Photo by Joe Ahlquist.

In addition to wheelchairs, the business also sells hospital beds, lifts for homes, hand controls for vans, ramps in houses—anything, really, that someone in a wheelchair needs or uses. Anything, really, to help give their customers their independence back.

“We’ve seen firsthand what great things people can do post-injury from Andy’s experience,” says grandson Drew. “We try and look at each patient like our dad or grandpa to give them the best life possible.”

Through the years, they’ve helped give that best life to patients from Byron to Brazil, from Minneapolis to the Middle East. Made lifelong friends of customers who’d come back year after year, decade after decade.

“The most rewarding thing,” adds son Jay, “is when you get people from other parts of the world. They’ve been crawling for 10 years. Crawling. That’s how they’re getting around. And you put them in a wheelchair. You put little kids who were in a manual chair in a power chair and they get to be free. That feels really good.”

It’s a feeling Andy’s been able to have for nearly 50 years. Which isn’t bad for a guy who was only supposed to live five more years.

Today, Andy Anderson is 85 years old. When asked for the secret to his longevity, he doesn’t pause. He points to his wife. “If it wasn’t for her,” he says, gesturing to his family and the showroom around him, “none of this would be here, and none of us would be here.”

At 81, the former nurse continues to do all of Andy’s home health care, as she has since the day he returned home after 18 months in the hospital back in 1964.

At 58 years post-injury and counting, the family believes Andy to be in the top 1% of longest-living quadriplegics.

“We’ve seen [Andy] overcome as severe a disability as anyone can have. ... He has been a great inspiration and a real help in our rehabilitation of other similarly disabled people.” — Dr. Robert Tinkham, in his letter of nomination for the Jaycees’ Outstanding Young Man award, which Andy won at age 35.

To this day, he continues to live an active lifestyle. “He comes in to the office weekly and talks to customers,” says Drew. Andy and Gretchen also continue to help out at Mayo Clinic, most recently mentoring and sharing their knowledge with new medical residents through monthly dinners or phone calls.

That doesn’t mean it’s all been smooth sailing. “Andy’s had a few health scares—including one last year that we didn’t know if he’d make it through,” says Drew. “It’s a testament to Gretchen for being an incredible wife and caregiver, and the Mayo Clinic for being there when we’ve needed them.”

And, arguably, a testament to one man’s positive attitude.

“I made a decision to live a full life to the best of my ability,” says Andy. “And that’s what I’ve done.”

Post Bulletin

Photo by Kevin Ness. Photo by Kevin Ness.

|

|